Expanding Normality at the Edges of the Art World in China

This is an in-depth interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer exploring the development, goals, and outcomes of the 2019 exhibition and symposium at the Harvard University Asia entitled Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan.

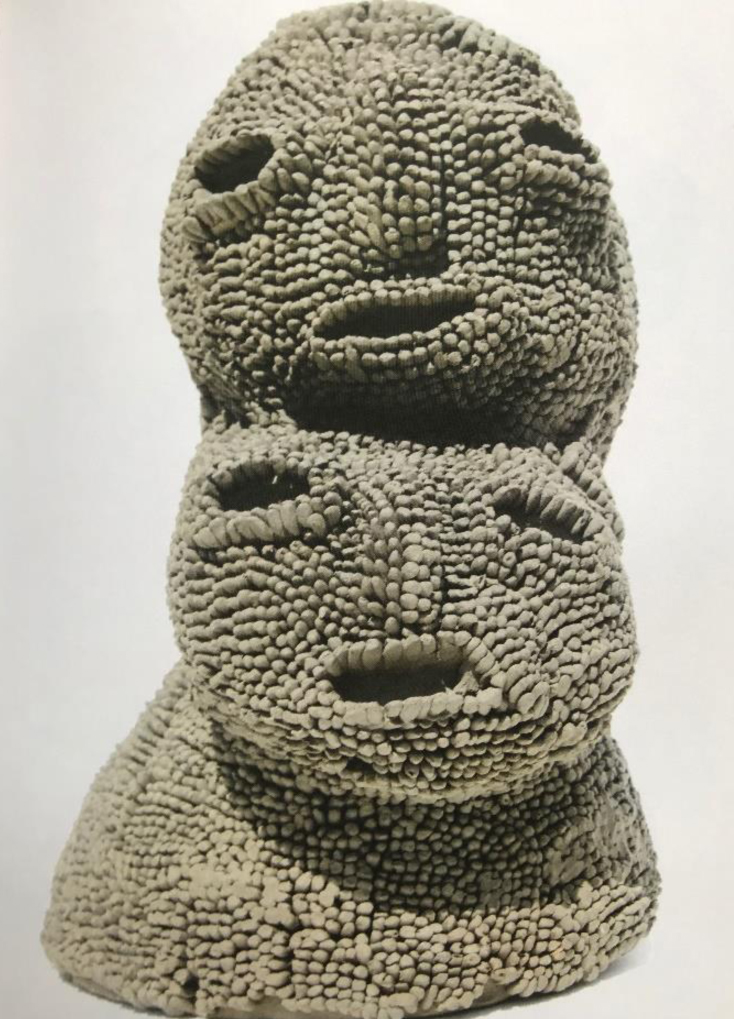

Keywords: artistic advocacy, stigma, disability, mental health, self-taught artists, outsider art, art brut, Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, Atelier Yamanami, Guo Haiping, Masato Yamashita

Shaun McNiff: Please tell us how you both came to exploring the art workshops in China and Japan; how you started to cooperate? How did the 2019 Harvard Asia Center exhibition originate and develop? What were your goals? Were there challenges? Are there particular people and institutions who helped make it possible?

Raphael Koenig: As we are working in the fields of Anthropology and Comparative Literature, respectively, it is very important for both of us to be able to exchange ideas with scholars who work specifically on issues related to the theory and practice of art therapy: so we are really grateful for your sustained interest in our exhibition.

Benny and I are both interested in exploring the margins of art, literature, and cinema, and focusing on lesser-known figures, movements, and phenomena that we feel are worthwhile: Benny is currently finishing his dissertation in Anthropology on the “edges” of the art world and entertainment industry in China, and I defended my dissertation in Comparative Literature, with a strong art historical component, on the relationship between the historical avant-gardes and self-taught art from the 1920s to the 1940s.

So, this project felt like a natural way of combining our respective approaches: I have been working on historical self-taught art, but was interested in looking into the innovative contemporary approaches developed by these specific art workshops. Benny has lots of experience conducting anthropological fieldwork, which involves engaging with local communities and participating in their daily routines while attempting not to disrupt them.

We felt that what was often missing in the description of art workshops for people with disabilities, and probably of self-taught artistic expression in general, was a more rigorous attention to their individual socio-historical contexts: bringing the conceptual and practical toolbox of anthropological fieldwork into a project that is informed by more theoretical discussions on self-taught art and is concerned with questions of artistic expression, creativity, disability, and individual agency felt like the right way to go. We hoped to shift the discourses on these workshops.